Peace and Justice are foundations that have been laid by others before we arrived upon the scene. Any efforts on my part are predicated upon this fact. Legacy is just that – peace is just that, a legacy of compassion and standing for one another, bearing witness, and standing in solidarity. The pieces represented here have been exhibited in other venues, yet the message of this particular work is the same. Strive for justice, seek the truth and speak to the heart of power, make a difference as you can be counted. Love your land, she is our mother, love one another, we are of one blood. – Meleanna.

Makua: Two Panels. Meleanna Meyer, 2007

On the Waianae Coast of Oahu, lies Makua Valley. Pre-contact, the valley—called “parent” in Hawaiian—was among of the most productive agricultural lands on the island. An ancient trail at the back of the valley went over the mountains into Waialua, connecting Makua to all parts of the island.

Of Makua’s Kamuakuopio Heiau, very little is left today. What remains is a raised sand platform, 120 ft. by 100ft., and two piles of large stones. Stones from the heiau were stolen in modern times to build rock fences. The Makua koa (fishing shrine), also in ruins, is said to lie in the middle of the beach. The Makua koa remains a much respected and honored spot to Hawaiian fisherman today.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army confiscated 6,600 acres in and around the valley to train troops for World War II, evicting the residents who lived there. The once-vibrant history, culture, environment and community were largely destroyed, as Makua was used as a bombing practice area by the U.S. military.

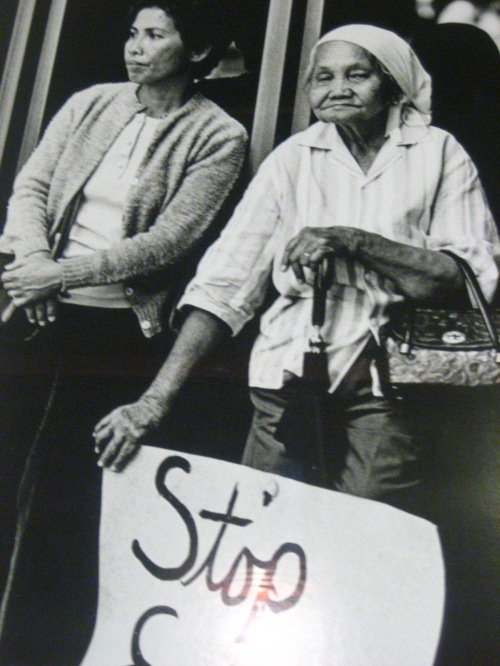

Yet, communities in Makua Valley today continue in their efforts to perpetuate their unique culture, protect their fragile natural environment, and resist the abuse of their land. Community resistance and protest ultimately halted bombing of the area in 1998.

Nonetheless, the military has continued to push to resume bombing practice in Makua Valley. Since 2003, live fire exercises have been prevented by court order. The valley is still home to many remaining sites and many native plants and animals in the 4,190-acre valley are still endangered.

The second panel in this pair of works displays ordnance collected from Makua Valley.

Born and raised, Ms. Meyer comes from Mokapu, O’ahu, and is the second child of Harry and Emma Meyer. She has had a lifelong love for the arts in all forms. She received her B.A.in design and photography from Stanford University. Meleanna was mentored by Nathan Oliveira and Leo Holub. Her kumu in mana’o Hawai’i is respected educator, Keola Lake. Meleanna received her MA in Educational Foundations from the University of Hawai’i at Manoa under the mentorship of Dr. Royal Fruehling. An East West Center grantee, APAWLI and Salzberg Fellow, she has been able to lend her many talents to a wide range of arts and culture collaborations. Ms. Meyer is a practicing artist, educator and filmmaker, and has taught in a wide range of educational settings both public and private, at the University level, in the charter schools, as an artist in residence and currently, contractually also as a consultant with Kamehameha schools Literacy and Instruction program as a arts/culture curriculum specialist. As a filmmaker she has three documentaries to her credit, is a published author and illustrator. Having received numerous awards for her visual art, her work also hangs in the State Museum, in the Honolulu City & County collection, with works in private collections both here and abroad.